Before Algebra Had a Name

When we think of algebra, many people picture European textbooks or Greek symbols. But long before that, in the land of Kemet in the Nile River Valley, Africans were already solving algebraic problems. Over 3,800 years ago, scribes in Kemet were writing and working through equations that involved unknown quantities, a fundamental concept of algebra.

One of the clearest examples comes from a document known as the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus, dating to around 1650 BCE. This papyrus contains dozens of problems that today we’d recognise as early algebra.

The “aha” and the Eye of Horus

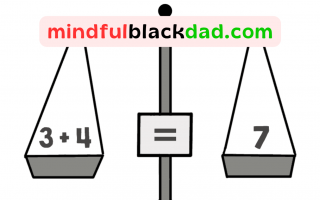

Kemetian algebra didn’t look like modern notation. Instead, scribes used terms like “aha”, meaning “quantity”, to represent unknown values. For example, one problem might say: A quantity and its seventh part together make 19. What is the quantity? This is essentially the equation x + x/7 = 19. The method used to solve it involved logical steps and mathematical structure.

This papyrus shows that In Kemet, mathematics was woven into daily life. Algebraic thinking was applied to architecture, agriculture, trade, and timekeeping.

A Legacy for Black Children

So algebra has deep African roots. For Black children, learning this history connects them to a long-standing tradition of intelligence, abstraction, and problem-solving.

Learn More

The Algebra of Ancient Egypt:

https://www.math.buffalo.edu/mad/Ancient-Africa/mad_ancient_egypt_algebra.html

[…] people hear the word “algebra”, they often think of secondary school, x’s and y’s, and complicated equations. But in truth, […]

[…] philosophy, politics and beyond. For example, the oldest known examples of algebraic thinking comes from Africa. This sort of information should be standard knowledge not just for Black people, but for […]

[…] The bone itself is a fibula (leg bone) from a baboon. It has three distinct columns of notches carved into its surface, arranged in deliberate groups. These markings are not random. They suggest early humans were tracking numbers, doubling values, identifying prime numbers, and possibly using a base-12 counting system. In short, it shows that mathematical awareness has deep roots in Africa. […]