The Ishango Bone, A Bone That Counts

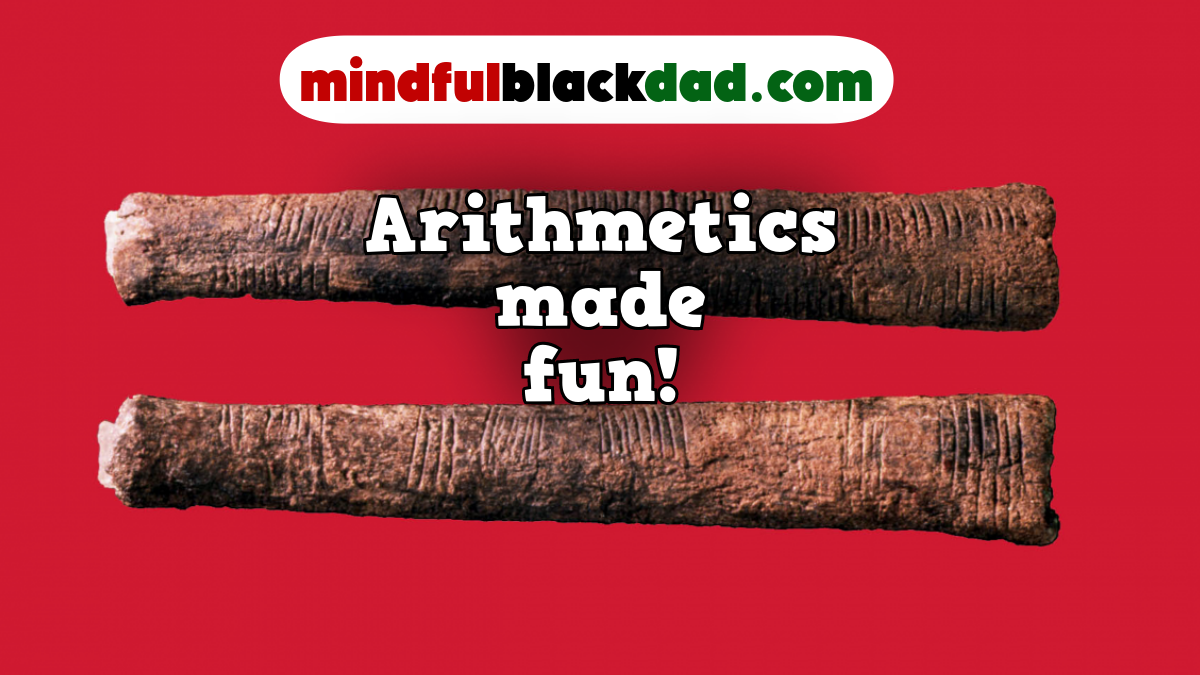

The Ishango Bone is one of the oldest known mathematical artefacts in the world, and it was created and used by Africans. Discovered in the 1950s near the headwaters of the Nile in the Democratic Republic of Congo near the Uganda border, it dates back at least 20,000 years. That’s a long time ago! To give some context, this is way earlier than than writing, which probably emerged about 5,000 years ago.

The bone itself is a fibula (leg bone) from a baboon. It has three distinct columns of notches carved into its surface, arranged in deliberate groups. These markings are not random. They suggest early humans were tracking numbers, doubling values, identifying prime numbers, and possibly using a base-12 counting system. In short, it shows that mathematical awareness has deep roots in Africa.

Mathematics Began in the Mind

What the Ishango Bone tells us is that mathematics began in the human mind, as a way of making sense of patterns in nature, time, and the world. The notches on the Ishango Bone suggest people were already experimenting with groupings, order, and structure, which are the foundations of mathematics today. It may have been used as a calendar, a tally stick, or even a teaching tool. Whatever its specific purpose, it reflects abstract thought and a culture that valued it.

Africa at the Centre, Not the Edge

Too often, Africa is left out of mainstream stories about the history of science and mathematics. But the Ishango Bone is a powerful reminder that Africa was not just involved — it was leading.

For children of African descent, learning about the Ishango Bone is another important strategy to help our children see mathematics as part of their story, from our deepest ancestral past, to the present and into the future that they will help create.

Learn More

Ishango Bone: The oldest mathematical artefact in the world